Introduction

When it comes to policing the Minnesota legislative process, the current Minnesota Supreme Court has gotten it wrong. Separately in Ninetieth Minnesota State Senate v Dayton,[i] and in Otto v. Wright County,[ii] the Minnesota Supreme Court ruled that there was no state constitutional violation either when the governor line-item vetoed the state legislature’s funding or when a law removed some of the state auditor’s functions, even though it was part of a much larger bill on state appropriations. The problem with these two decisions is that it effectively exacerbates political polarization in state government and encourages both the governor and legislature to engage in winner-take-all politics.609, 623 (Minn. 2017).

David Schultz

Professor of Political Science, Hamline University; Visiting Professor of Law, University of Minnesota.

Both the Dayton and Wright County cases need to be examined together in terms of the constitutional clauses and principles they represent. In Dayton at issue was Article IV, Section 23 of the Minnesota Constitution that declares, “[i]f a bill presented to the governor contains several items of appropriation of money, he may veto one or more of the items while approving the bill.” This provision of the constitution grants the governor line-item veto for appropriations bills, similar to what a total of forty-three states provide.[iii] Article IV, Section 17, of the Minnesota Constitution states, “[n]o law shall embrace more than one subject, which shall be expressed in its title.” Minnesota, similar to what is found in approximately forty other states,[iv] mandates that a specific bill or law include only one subject. Both the line-item veto and single-subject rules emerged in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as part of Populist and Progressive Era reforms to address the perceived corruption of state legislative politics by special interests.[v] Three reasons can be identified to support their adoption.

The first was to prevent legislative mischief whereby bills are loaded up with a lot of unrelated provisions in the hope legislators could force others, including the governor, to support provisions they might not want by connecting them to proposals they did support. This is known as logrolling.[vi] The single-subject rule did this for policy bills, the line-item veto did this for appropriation bills.

The second reason was single-subject rules preserve a meaningful role for the governor’s veto. Minnesota governors can line-item veto budget items in bills, but not policy. Violations of the single-subject rule force the governor into a take it or leave it approach when it comes to vetoes. Such an approach does not foster cooperation between the executive and legislative branches. To pass legislation, agreement between the legislature and governor are needed.

Finally, single-subject rules were put in place to prevent voter confusion and deception. If bills embrace only one subject, then it is easier for voters and the public to follow and know what legislators are doing. Collectively, vigilant enforcement of the single-subject rule for policy bills and the use of the line-item veto for appropriations fostered good government in terms of promoting gubernatorial-legislative cooperation and transparency for the public.

Early on in Minnesota’s history, the courts took an aggressive approach to enforcing the single-subject rule, forcing the legislature to behave.[vii] But for most of the twentieth century the courts backed off from enforcing the clause, with only about five laws ever invalidated under the single-subject rule.[viii] The result being regardless of partisan affiliation—the legislature simply ignored the rule with impunity. There was a brief, recent period involving cases such as Unity Church of St. Paul v. Minnesota[ix] and Associated Builders and Contractors v. Ventura,[x] where the Minnesota courts aggressively enforced the single-subject rule, striking down legislation as a violation of Article IV, Section 17. In the Associated Builders case, it was the product of a DFL-controlled House and Senate in 1997 teaming up against Republican Governor Arne Carlson, producing an omnibus budget bill with 247 pages, 16 articles, and an 850 word title![xi]

However, the legislature did not learn its lesson and it continued to jam more and more things into single bills. Often this occurred, as seen in the last few decades, when Minnesota experienced divided government and partisan polarization that paralleled what was seen at the national level.

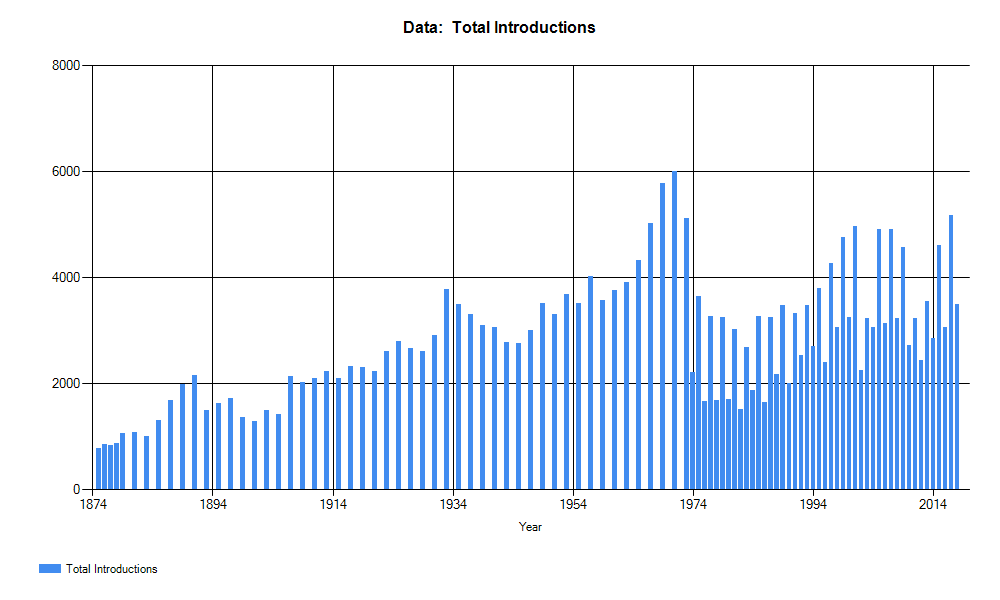

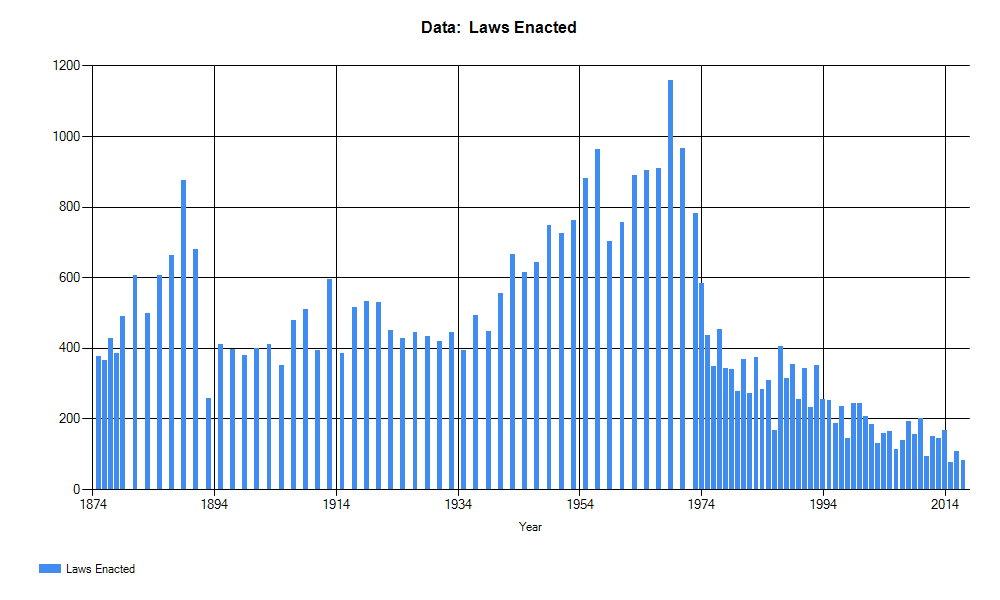

Consider these two charts. The first looks at total bill introductions in the Minnesota Legislature over time,[xii] the second looks at total laws enacted.[xiii] Since 1974 the pattern on total introductions has not changed much (accounting for the fact that more bills are introduced in the first year of a biannual process), but total laws enacted has gone down. Clearly some of this perhaps reflects fewer bills being signed into law by the governor (a sign of divided government and polarization),[xiv] but it also speaks to how over time more and more bills are placed into larger omnibus legislation which raises concerns about the single-subject rule. Additionally, placing more and more policy into a single bill does something else too—it is an effort to circumvent the governor’s regular veto power by forcing him to accept or reject a bill in toto.

Wright County and Dayton enable this bad behavior. In the former case the Minnesota Supreme Court refused to provide any meaningful limits on what would be considered a violation of the single-subject rule, encouraging the legislature, especially if it is from a different political party compared to the governor, to pack legislation with as much divergent policy as it wants and force the governor into an all or nothing or take it or leave it approach. This is exactly what happened in 2018 when the legislature sent the governor a nearly 1,000 page omnibus bill that contained almost all of the bills from the session, and the governor vetoed it.[xv] Effectively the 2018 session was for naught.

The Dayton decision empowers an all or nothing approach in a different way. In upholding the ability of the governor to line-item veto the legislature’s funding, it permits the governor to extort the latter. Specifically, “Do what I want, or I will zero out your funding.” This approach is akin to the popular phrase of someone taking their bat and ball and going home if they do not get their way.

Taken together, the Wright County and Dayton decisions do no more than reinforce and encourage bad behavior and politics at the Minnesota State Capitol. There is every incentive, even in 2019 where the House is controlled by the Democrats and the Senate by the Republicans, to enact large omnibus bills in each chamber, seek to force each side to agree to them, and then strong arm the governor to sign them. In turn, the governor has every incentive to use the line-item veto as a blunt cudgel to try to force the legislature into submission.

Overall, the Minnesota Supreme Court failed to understand the reasons for the line-item veto and single-subject rules in the state constitution in terms of structuring the legislative process. Institutional rules matter, and if there is no incentive to cooperate then cooperation will not occur. The Minnesota Supreme Court’s decisions in the Dayton and Wright County cases either were blind to the way polarization has warped state politics and how contrary decisions could have gone a long way to fixing the problem, or one can argue that these decisions have simply taken a bad situation and made it worse. Look to see in 2019 and future sessions how these two cases will seriously impact and distort Minnesota politics.

[i] 903 N.W.2d 609, 623 (Minn. 2017).

[ii] 910 N.W.2d. 446, 455 (Minn. 2018).

[iii] Gubernatorial Veto Authority with Respect to Major Budget Bill(s), Nat’l Conference of State Legislatures (Dec. 2008), http://www.ncsl.org/research/fiscal-policy/gubernatorial-veto-authority-with-respect-to-major.aspx [https://perma.cc/FV9J-PP8L].

[iv] Single Subject Rules, Nat’l Conference of State Legislatures (May 8, 2019), http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/single-subject-rules.aspx [https://perma.cc/P8G3-JUWP].

[v] William Bennett Munro, The Initiative, Referendum, and Recall 16–20 (1913); Richard Hofstadter, The Age of Reform: From Bryan to F.D.R. 5–6 (1955); David Schultz, Election Law and Democratic Theory 123–25 (2014).

[vi] Nancy J. Townsend, Single Subject Restrictions as an Alternative to the Line-Item Veto, 1 Notre Dame J.L. Ethics & Pub. Pol’y 227, 231 (1985). See also Unity Church of St. Paul v. Minnesota, 694 N.W.2d 585, 592 (Minn. Ct. App. 2005).

[vii] See State v. Cassidy, 22 Minn. 312, 322 (1875); Johnson v. Harrison, 50 N.W. 923, 924 (Minn. 1891).

[viii] Unity Church of St. Paul, 694 N.W.2d at 597 (Minn. Ct. App. 2005).

[ix] 694 N.W.2d 585 (Minn. Ct. App. 2005).

[x] 610 N.W.2d 293 (Minn. 2000).

[xi] Id. at 297.

[xii] Graph Historical Data – 1875 to Present, Minn. Legislative Reference Library, https://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/histleg/hist_chart?yearorbi=year&bi1=1874&bi2=2014&hintro=n&sintro=n&tintro=n&laws=y&res=n&percent=n&year1=1875&year2=2017&custom=y&size=m (last visited Mar. 23, 2019).

[xiii] Id.

[xiv] David A. Schultz, Minnesota: The Loyal Blue State of Minnesota Turning Purple, in David A. Schultz & Rafael Jacob, Presidential Swing States 357, 371 (2018).

[xv] Jessie Van Berkel, Gov. Mark Dayton vetoes tax, spending bills, Star Tribune, May 23, 2018, at 1.