New President and Dean Camille Davidson comes from a family of teachers, and she’s committed to helping students find their purpose through legal education

President and Dean Camille M. Davidson

In the spring of 1998, after a long legal battle, the state of Mississippi released the records from its infamous Sovereignty Commission. The nearly 125,000 pages of files detailed 17 years of state-sanctioned spying, harassment, infiltration, and other measures beginning in the mid-1950s designed to stop the spread of civil rights and maintain segregation.

Camille Davidson’s father was in the report; her uncle was also listed among those the state surveilled. Even more shocking was that her dad’s parents were listed as “future possible agitators,” Davidson said, “simply because they were middle-aged Black people in Mississippi in the ’60s who chose to exercise their right to vote.” It was “jarring,” she said, to learn that their neighbors, people she had known all her life, had been interviewed by agents of the state about her grandparents: Were they good citizens? Could they be trusted?

The subject is still difficult for her to talk about—the hatred and suspicion her parents and grandparents endured at the hands of the state, the sacrifices they made so that later generations would have it better.

But it made the importance of her chosen profession—the law—abundantly clear.

“It helps me to remind students of thinking about the why: why you’re in law school, why you’ve chosen law school, and what it is that you want to do with your law degree. I think law is the one profession where individuals really can make a difference. Democracy is fragile, it’s only as strong as any of us allow it to be, and so to be a part of the solution rather than the problem is important for me.”

A call to teach

Camille, age 1, in Oxford, Mississippi

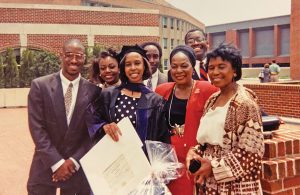

Davidson was born and raised in Oxford, Mississippi. Her parents were both educators, which meant teaching was the last thing she thought she’d ever do. She headed off to Millsaps College in Jackson, a few hours south of her hometown, and earned a degree in business administration magna cum laude in 1989. After a year of study at the University of Nairobi in Kenya, her plan was to go to law school and become a tax attorney. But as she settled in at Georgetown University Law Center, she found herself drawn to opportunities like teaching Street Law to students in local high schools and working in a pre-college prep program aimed at students from underrepresented backgrounds. “Even though I was running away from education, I think it was always there,” she says.

After graduating from Georgetown Law, she clerked at the D.C. Superior Court and spent six years in the Office of Legislative Counsel at the U.S. House of Representatives, helping draft the HIPAA legislation among other duties. She married her husband, Trevor Fuller, in 1996, and the two moved to Charlotte, North Carolina, for his work as an employment law litigator. There she began practicing as an estate-planning attorney. She found what she most enjoyed were the “front-facing” parts of that job, working with nonprofits, churches, and community groups on their financial and legal plans. That experience nudged her further toward teaching, and in 2004 she took the plunge and accepted a part-time gig teaching Introduction to Political Science at Davidson College.

She was still working full time as an attorney, and she and her husband were raising two young children, Jackson and Schuyler, and soon it became obvious that she needed to pare down. It turned out that education—her family legacy and the work she’d felt called to since law school—was also the best choice for her career and family.

“I remember the day I decided to step away from practice,” she said. “My husband and I both had oral arguments before the 4th Circuit in Richmond scheduled for the same day. I had flown in my sister, who was single at the time, to watch the kids. I remember walking out of court and I got a call from school. Our son, who was in kindergarten, was sick, and I was four hours away. I thought, ‘Superwoman is a myth. I cannot be all things to all people at all times.’ For me, it was a personal decision to figure out how I could continue in the profession that I loved but also have some balance for me to raise and enjoy my family. If there was ever a moment, that was probably the moment.”

A home in legal education

Charlotte School of Law opened in 2006 and hired Davidson as the first adjunct in the spring of 2007. She taught legal writing and loved it, so she applied for a full-time position and eventually became a tenured professor. “Teaching is probably one of the best careers possible,” she said. “You get to think, you get to focus on your scholarship, you teach your awesome classes.”

And because it was a startup law school, she did a bit of everything: teaching first-year classes and upper-level electives, starting a clinical lab, helping create two summer programs. That hands-on experience would be invaluable later as a dean in working with faculty across a range of specialties.

She moved into administration about halfway through her time at Charlotte Law, serving as associate dean for academic affairs and faculty development. This brought a new set of moving pieces to manage and a huge amount of learning, even in adverse circumstances. The school ran into difficulties and wound up closing in 2017. She praised the faculty at Charlotte Law—“they performed miracles every day”—and took two main lessons from the experience: Address conflict head-on and be transparent. “I share—I share good news, I share not good news. I think everybody needs to be on the same page, and I don’t think it benefits anybody when we hide information.”

A fundraising record

Camille at Dala Hill in Kano, Kano State, Nigeria, 1990

After Charlotte Law closed, Davidson taught as an adjunct at Wake Forest University School of Law and then served as a judicial hearing officer. She became dean of Southern Illinois University School of Law in July 2020—the first Black woman to hold that job. (She is also the first Black woman to serve as president and dean at Mitchell Hamline or any of its predecessor schools.)

She started at SIU Law at the height of Covid. Along with addressing the challenges of the pandemic, the school needed to expand the admissions pool and shore up financial support. With no professional fundraising experience and minimal staff, Davidson started calling people, emailing, and setting up Zoom meetings. She started with the law school’s first class—which entered in 1973—and built from there. “As I met with alums I listened. I listened a lot. I listened to what made them happy, I listened to what they enjoyed about their law school experience.” She secured one gift to fund a summer pipeline program for prospective students and another from an alum, a trial attorney, who named a courtroom at the school after her longtime partner.

She also held conversations with John Simmons, who earned his undergraduate degree from the Edwardsville campus of SIU. Although he was not a law school alumnus, as a practicing attorney in southern Illinois he saw great potential in SIU Law as a source of legal talent to strengthen the region, and over a few years of conversations with Davidson, it became clear this was in perfect sync with her view. Rather than try to outcompete the elite schools, Davidson said, “I felt like we needed to recognize that here’s who we are, here’s our impact, and let’s let our light shine.” Simmons and his wife decided to donate $10 million to the law school, the largest gift in the university’s history. The school has been renamed the SIU Simmons Law School.

“In our very first meeting, John committed to hiring two students for a summer internship with his firm as a way to build a pipeline. We continued to talk about the law school,” Davidson said. “Ultimately I think it was him putting trust in our vision and seeing the impact the school had in producing lawyers to serve the region.

“I believe so much in the power of relationships and listening,” she said. “If I have a superpower, it is probably the ability to connect with pretty much all people. I’m going to find a connection in some sort of way, and probably after we sit down and talk for a half hour we’re going to figure out where our lives have intersected and what we have in common. So that’s been my strength as a fundraiser.”

The draw to Mitchell Hamline

Camille with her family at her graduation from Georgetown Law, 1993

Davidson, who turns 57 in July, saw in Mitchell Hamline “the best of two things that were important to me”—a trusted source of legal talent for the state and region as well as the national leader in innovative approaches to legal education. She called blended learning “the cutting edge of the future of legal education that has extended access to many who would have had no other way to earn a J.D. So many schools are trying to figure out how to do hybrid and online delivery of legal education, but the blended program to me is the standard which so many other law schools are looking at as a how-to manual.”

The other strong draw to Mitchell Hamline was the chance to lead an independent law school. After learning the fundamentals of legal teaching and administration at Charlotte Law and then leading a law school at SIU but within the larger university system, she’s excited by the opportunity to lead a freestanding law school, in partnership with the board of trustees, especially one committed to making it possible for all kinds of people from all kinds of backgrounds, geographies, and life situations to figure out their own “why” through the study of law.

“The only way to have real access to justice is to train folks from a particular community so that they’re really able to provide the resources to their community. Mitchell Hamline’s different pathways provide so many opportunities for folks to join us in the profession.”