Brian Owsley is an asssociate professor of law at UNT Dallas College of Law. The views expressed in this article are entirely his own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Mitchell Hamline Journal of Public Policy and Practice.

Article by Professor Brian Owsley

Recent reporting raised concerns about the United States Supreme Court and its ethics. The Code of Conduct for United States Judges applies to all federal judges with the exception of Supreme Court justices.[1] Many have demanded that the Supreme Court police themselves or for Congress to establish a code of conduct applicable to the Supreme Court.[2]

Several Democrats recently have questioned in strong terms the Court’s ethics. For example, Senator Ed Markey asserted that “[e]ach scandal uncovered, each norm broken, each precedent-shattering ruling delivered is a reminder that we must restore justice and balance to the rogue, radical Supreme Court” in proposing legislation to expand the Court.[3] Similarly, Senator Sheldon Whitehouse chided that “[t]he court has been captured by special interests much in the manner of a 19th-century railroad commission captured by the railroad barons.”[4] Representatives Cori Bush and Katie Porter both characterized the Supreme Court as corrupt.[5]

Of course, others stepped up to defend the Supreme Court based on allegations of ethical lapses.[6] In the wake of these allegations, Senator Mike Lee not only defended Justice Thomas, but characterized him as a hero.[7]

This essay addresses these recent ethical concerns in Section I. In Section II, it notes some potential solutions unlikely to work today. Section III proposes a solution to reduce Supreme Court staffing as a means to influence the justices. In Section IV, the essay addresses the congressional Spending Clause Power to achieve this proposed solution.

I. Recent Revelations Placed The Supreme Court In The Public Spotlight Over Ethical Concerns.

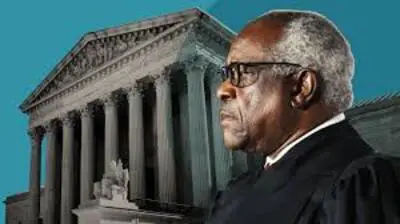

Recent concerns about ethics at the Supreme Court began with revelations that billionaire Harlan Crow took Justice Clarence Thomas and his wife on a vacation. Specifically, in June 2019, Crow hosted the Thomases by flying them on a private jet to Indonesia where they took a superyacht around various Indonesian islands attended to by various servants and a private chef that is estimated to cost over $500,000.[8] This largesse by Crow to Justice Thomas occurred for twenty years without reporting by Justice Thomas.[9] He failed to disclose various gifts from other benefactors, including now-deceased billionaire Wayne Huizenga, Apex Oil CEO Paul Novelly, and David Sokok, a former Berkshire Hathaway executive.[10]

These same ProPublica reporters then revealed a week later that Crow purchased Justice Thomas’ Savannah, Georgia childhood home as well as two nearby vacant lots in 2014 for $135,000.[11] Crow then renovated the home where Justice Thomas’ mother continues to reside to this day.[12] On August 9, 2023, Justice Thomas reported the purchase by Crow in his Judicial Disclosure Report, explaining that he “inadvertently failed to realize that the ‘sales transaction’ for the final disposition of the three properties triggered a new reportable transaction in 2014, even though the sale resulted in a capital loss” notwithstanding the obligation to report the loss.[13]

Justice Thomas explained that he received advice that he did not have to disclose the vacations because Crow was an old friend and did not have any litigation before the Supreme Court.[14] He also failed to disclose Crow’s purchase of the Savannah properties.[15]

Next, the ProPublica reporters published an article that Harlan Crow paid the private school tuition for Justice Thomas’ grandnephew for whom he had legal custody and essentially considers a son.[16] It is unclear the exact amount but it could be as high as $150,000. Although Justice Thomas failed to report the gifts to his grandnephew, he did report a smaller gift of $5,000 to the same child.[17]

In August 2023, the New York Times reported that Justice Thomas received a loan from Anthony Welters, a friend, to buy a used luxury recreational vehicle for $267,230.[18] Justice Thomas failed to disclose the loan or whether the loan carried any interest.[19] Welters indicated that the loan was “satisfied” in about 2008, but it is unclear whether that meant Justice Thomas paid it off or it was forgiven.[20]

In a similar revelation, Justice Neil Gorsuch sold rural Colorado property that he owned to Brian Duffy, the chief executive officer of the international law firm Greenberg Traurig.[21] Duffy, whose firm has an extensive Supreme Court practice, acquired the property just after Justice Gorsuch was confirmed in 2017 after it had been on the market for almost two years.[22]

Concerns about ethics by Supreme Court justices is by no means only a concern with conversative justices. For example, Justice Sonia Sotomayor failed to recuse herself from two cases before the Court, both involving her publisher Penguin Random House.[23] Notwithstanding receiving over three million dollars from the publisher, she did not recuse when parties suing it sought Supreme Court review.[24] Justice Gorsuch who also has earned hundreds of thousands of dollars from his book deal with the same publisher failed to recuse himself for the same cases occurring since he joined the Court.[25]

The failures to disclose or recuse by Supreme Court justices is not new. In 2004, Justice Antonin Scalia denied a motion that he recuse himself in a case before the Court involving Vice President Richard Chaney.[26] He rejected the notion that his long-standing friendship with Vice President Cheney and their duck hunting trip did not create a situation in which his impartiality might be questioned.[27]

It is not that these ethical lapses are exclusively reserved for the Supreme Court Justices. For example, Representative Lois Frankel revealed that she sold First Republic Bank stock before federal regulators seized it.[28] Moreover, she purchased JPMorgan stock just before it acquired First Republic Bank’s assets.[29] Although she disclosed and is not being investigated, the reporting raised concerns about Congressional ethics.

II. Some Potential Solutions Currently Have Limited Likelihood Of Success.

Here, with the various allegations against Justice Thomas, there are potential violations of federal law. Thus, Attorney General Merrick Garland could conduct an investigation that might lead to criminal charges. Although there might be a good argument that Justice Thomas broke the law, it seems unlikely that Garland will take the steps leading to an indictment.

Another option is impeachment. As one commentator asserted, “[t]here’s not a ton that Congress can do about Thomas, or any justice who appears to be engaging in questionable ethical conduct, because the nature of the court is to be self-governing.”[30] In an interview, Justice Alito boldly declared that “[n]o provision in the Constitution give[s] [Congress] the authority to regulate the Supreme Court—period.”[31]

Congress has not impeached a Supreme Court justice since 1804 when it impeached Samuel Chase at the behest of President Jefferson due largely to political disputes.[32] The Senate’s acquittal of Justice Chase led to increased judicial independence for the Supreme Court.[33] Since that time, Congress has impeached only a few federal judges. [34] Given that the Republicans control the House of Representatives, it is highly unlikely that Justice Thomas will be impeached.

In March 2019, Justices Samuel Alito and Elena Kagan testified before Congress regarding budgetary matters.[35] During her testimony, Justice Kagan explained “that Chief Justice Roberts ‘is studying the question of whether to have a code of judicial conduct that’s applicable only to the United States Supreme Court.”[36]

To date, Chief Justice Roberts still appears to be studying the issue. Senator Dick Durbin requested that Chief Justice Roberts provide testimony before the Senate.[37] However, he declined the invitation, citing separation of powers concerns regarding such an appearance. Of course, other Supreme Court Justices have testified for Congress. In addition to Justices Alito and Kagan in 2019, Justices Breyer and Kennedy testified together in 2015 before the House Appropriations Committee.[38] Moreover, Justices Scalia and Breyer testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee in 2011.[39]

Although Justice Alito’s argument that Congress cannot compel the Supreme Court to adhere to an ethics code is based on a narrow interpretation of separation of powers principles,[40] that does not end the discussion. Congress has options regarding concerns about judicial ethics for the Supreme Court. Consistent with separation of powers, it controls the power of the purse pursuant to its Spending Clause Powers. Just as justices have testified before Congress to promote the Court’s budgetary needs and projects, Congress can use its control to reduce the Court’s budget to pressure the justices to engage in some reform.

III. Congress Could Encourage The Supreme Court To Develop An Ethical Code By Reducing Its Support Staff.

The nine justices receive assistance and support from a number of employees. Congress can reduce this support in ways that would make the justices’ work more personally demanding.

Currently, the justices employ about four judicial law clerks each term to assist them in research and drafting opinions regarding the matters before the Court with the Chief Justice entitled to a fifth law clerk.[41] The tradition on employing law clerks began in 1882 when Justice Horace Gray hired one.[42] He brought this practice with him to the Supreme Court from his tenure as chief judge of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court.[43] Justice Gray paid for these law clerks out of his own pocket for his first three years on the Supreme Court.[44] In 1886, Congress enacted legislation providing funds for each justice to hire a clerk.[45]

Although justices may been initially reluctant to use law clerks, the justices quickly warmed to the idea. Over time, the number of law clerks grew. Currently, Congress authorizes “[t]he Chief Justice of the United States, and the associate justices of the Supreme Court [to] appoint law clerks and secretaries whose salaries shall be fixed by the Court.”[46] The justices invariably rely significantly on these law clerks to perform the Court’s work.[47]

Judicial law clerks are not the only employees at the Supreme Court authorized by Congress. Over five hundred people work at the Supreme Court: librarians, administrative assistants, clerks, as well as the marshal.[48] Each justice gets two administrative assistants as well as a messenger.[49]

Congress authorized the Supreme Court to hire a librarian who in turn may hire assistant librarians approved by the Chief Justice.[50] The Supreme Court Library employs about twenty-nine staff members to assist the Court.[51] Similarly, Congress authorized the Supreme Court to hire a Clerk of the Court as well as deputies.[52] Currently, there are over thirty such employees working at the Supreme Court.[53] The Clerk of the Court may hire necessary messengers and assistants subject to the Chief Justice’s approval.[54] Additionally, per statute, the Supreme Court hires a reporter who in turn may hire “necessary professional and clerical assistants and other employees” to assist the Court in releasing and publishing decisions.

The Chief Justice also receives a Counselor who functions as the chief of staff “serv[ing] at the pleasure of the Chief Justice and [] perform[ing] such duties as may be assigned to him by the Chief Justice.”[55] This person “supports the Chief Justice as head of the federal judiciary, working in partnership with court executives and judges on matters of judicial administration, and as liaison to the executive and legislative branches on issues affecting the Court.”[56]

Congress officially created the position of Counselor in 2008.[57] However, the role had an earlier history dating back to 1946 when Chief Justice Fred Vinson hired an administrative assistant.[58] Chief Justice Warren Burger explained that “[t]he office of the chief justice desperately needs a high-level administrative deputy or assistant. I devour four to six hours a day on administrative matters apart from my judicial work.”[59]

Finally, Congress authorized the Court to appoint a Marshal who has a number of various duties.[60] Specifically, she disburses various funds for Court-related expenses, including the salaries of all Court employees, even the justices.[61] She oversees the proceedings before the Court as well as executes any orders issued by the justices.[62] Significantly, she supervises the Court’s police force who provide security for the justices.[63] Indeed, the Marshal directly supervises about half of the Court’s employees, including over 160 officers who provide security.[64]

Chief Justice Roberts declined to appear before the Senate Judiciary Committee to discuss ethics for the justices, citing separation of powers as his justification. Congress has checks and balance over the judiciary in a number of ways. For example, the Senate confirms the President’s nominations to the federal bench.[65] Moreover, Congress can limit the number of judges, including the number of Supreme Court justices.[66] As previously noted, the House of Representatives can issue articles of impeachment against federal judges based on high crimes and misdemeanors, and the impeached judges are tried before the Senate.[67]

Congress Can Affect Supreme Court Staffing Based On Its Spending Clause Power.

Another check that Congress has on the judiciary, including the Supreme Court stems from its Spending Clause Powers: “The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States.”[68] In controlling the power of the purse, Congress can influence the Court’s actions by reducing its budget. In United States v. Butler, the Court acknowledged that the Constitution provided Congress with broad powers to tax and spend money for the general welfare: “the power of Congress to authorize expenditure of public moneys for public purposes is not limited by the direct grants of legislative power found in the Constitution.”[69]

In 1984, Congress enacted legislation ordering the Secretary of Transportation to withhold five percent of federal highway funds from states that did not adopt a twenty-one-year-old minimum drinking age to enhance safety on the nation’s roadways. South Dakota allowed individuals nineteen years and over to purchase beer with up to 3.2 percent alcohol.Consequently, the Department of Transportation informed South Dakota that it would withhold approximately five percent of the federal highway funds earmarked for the state. South Dakota filed an action challenging the law.

In Dole, the Court grappled with whether Congress exceeded its spending clause powers by enacting legislation conditioning the award of federal highway funds on the adoption by a state of a uniform minimum drinking age.[70] Pursuant to the Spending Clause Power, Congress can condition the receipt of federal funds upon specific actions by the recipient.[71] This power is not without limits as, for example, the congressional goals must pursue the general welfare.[72] The Supreme Court established that federal courts must defer to congressional judgment in determining whether specific legislation serves the general welfare.[73] Thus, courts can only reject this congressional determination when Congress “is clearly wrong, a display of arbitrary power, not an exercise of judgment.”[74]

Congress, acting indirectly to encourage uniformity in state drinking ages, was within constitutional bounds. The Court found that the legislation was in pursuit of “the general welfare,” and that the means chosen to do so were reasonable. The five percent loss of highway funds was not unduly coercive.

V. Conclusion

As a former federal magistrate judge assigned a single clerk at a time, I experienced their extremely beneficial assistance directly. If Congress reduced the number of law clerks that each justice could hire, that would have adverse consequences on their workload. A reduction of law clerks may have the additional benefit of reducing the number of concurring and dissenting opinions as well as the length of decisions overall.

If Congress reduced the number of Supreme Court employees that each justice could hire, that would likely lead them to reassess whether it is time for the Court to have an ethical code. I am not recommending that Congress reduce employees dedicated to security for the justices and the building. With over five hundred employees, however, there are plenty of ways that the Congress can find some reductions in staffing.

Indeed, it provides a win for everyone. Democrats get to promote a change to the ethical lapses that they raised. Republicans get to find bipartisan ways by which to reduce the budget through staff cuts. The public gets to have a renewed faith in the Supreme Court’s integrity based upon a new standard of ethics directly applicable to the Court.

[1] Russell Wheeler, Justice Thomas, gift reporting rules, and what a Supreme Court code of conduct would and wouldn’t accomplish, Brookings (May 1, 2023), https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2023/05/01/justice-thomas-gift-reporting-rules-and-what-a-supreme-court-code-of-conduct-would-and-wouldnt-accomplish/.

[2] Id.

[3] Press Release, Sen. Markey, Rep. Johnson announce legislation to expand Supreme Court, restore its legitimacy, alongside Sen. Smith, Reps. Bush and Schiff, Off. of Ed Markey, U.S Sen. of Mass. (May 16, 2023), https://www.markey.senate.gov/news/press-releases/05/16/2023/sen-markey-rep-johnson-announce-legislation-to-expand-supreme-court-restore-its-legitimacy-alongside-sen-smith-reps-bush-and-schiff.

[4] Edward Fitzpatrick, Senator Whitehouse: Chapter and verse on how the US Supreme Court was ‘captured,’ Boston Globe (Oct. 20, 2022), https://www.bostonglobe.com/2022/10/20/metro/senator-whitehouse-chapter-verse-how-us-supreme-court-was-captured/.

[5] David Leonhardt, Supreme Court Criticism, N.Y. Times (May 22, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/22/briefing/supreme-court-criticism.html.

[6] James Taratino, Justice Clarence Thomas and the Plague of Bad Reporting, Wall St. J. (Apr. 20, 2023), https://www.wsj.com/articles/justice-thomas-and-the-plague-of-bad-reporting-propublica-washington-post-disclosure-court-safety-def0a6a7.

[7] Bridger Beal-Cvetko, Sen. Mike Lee defends Clarence Thomas amid ethics scandal, calls justice a ‘hero,’ KSL (Apr. 17, 2023), https://www.ksl.com/article/50623178/sen-mike-lee-defends-clarence-thomas-amid-ethics-scandal-calls-justice-a-hero; see also Stephen L. Carter, Demand Ethics from Congress, Too, Not Only the Supreme Court, Bloomberg (May 14, 2023), https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2023-05-14/congress-has-more-ethical-problems-than-the-supreme-court-does?leadSource=uverify%20wall.

[8] Joshua Kaplan, et al., Clarence Thomas and the Billionaire, ProPublica (Apr. 6, 2023), https://www.propublica.org/article/clarence-thomas-scotus-undisclosed-luxury-travel-gifts-crow.

[9] Id.

[10] Alison Durkee, Clarence Thomas: Here Are All The Ethics Scandals Involving The Supreme Court Justice Amid Latest ProPublica Revelations, Forbes (Aug. 10, 2023), https://www.forbes.com/sites/alisondurkee/2023/08/10/clarence-thomas-here-are-all-the-ethics-scandals-involving-the-supreme-court-justice-amid-latest-propublica-revelations/?sh=1e60b172df6d.

[11] Joshua Kaplan, et al., Billionaire Harlan Crow Bought Property From Clarence Thomas. The Justice Didn’t Disclose the Deal, ProPublica (Apr. 13, 2023), https://www.propublica.org/article/clarence-thomas-harlan-crow-real-estate-scotus.

[12] Id.; Shirin Ali, Clarence Thomas’ Mom Definitely Still Lives in the House the Billionaire Bought, Slate (Apr. 13, 2023), https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2023/04/clarence-thomas-mom-billionaire-house.html.

[13] Financial Disclosure Report For Calendar Year 2022 by Clarence Thomas, at 8 (Aug. 9, 2023), https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/23932793-clarence-thomas-2022-financial-disclosure; Ariane de Vogue & Devan Cole, Clarence Thomas officially discloses private trips on GOP donor Harlan Crow’s plane, CNN (Aug. 31, 2023), https://www.cnn.com/2023/08/31/politics/thomas-alito-supreme-court-disclosures/index.html.

[14] Ariane de Vogue, Company with ties to GOP megadonor and longtime friend of Justice Thomas had business before Supreme Court, CNN (Apr. 25, 2023), https://www.cnn.com/2023/04/25/politics/clarence-thomas-harlan-crow-supreme-court/index.html.

[15] Jared Gans, Thomas failed to disclose real estate deal with GOP donor who also paid for lavish trips: report, The Hill (Apr. 13, 2023), https://thehill.com/regulation/court-battles/3949237-thomas-failed-to-disclose-real-estate-deal-with-gop-donor-who-also-paid-for-lavish-trips-report/; Clarence Thomas sold real estate to donor but didn’t report deal, report says, CBS News (Apr. 14, 2023), https://www.cbsnews.com/news/clarence-thomas-sold-real-estate-to-donor-didnt-report-deal/.

[16] Joshua Kaplan, et al., Clarence Thomas Had a Child in Private School. Harlan Crow Paid the Tuition, ProPublica (May 4, 2023), https://www.propublica.org/article/clarence-thomas-harlan-crow-private-school-tuition-scotus; Aaron Blake, The brazen explanation for concealing the Ginni Thomas payment, Wash. Post (May 5, 2023), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2023/05/05/clarence-thomas-ginni-leonard-leo/.

[17] Blake, supra note 17.

[18] Jo Becker & Julie Tate, Clarence Thomas’s $267,230 R.V. and the Friend Who Financed It, N.Y. Times (Aug. 5, 2023); Charles R. Davis, Clarence Thomas purchased his luxury RV with the help of a wealthy former healthcare executive: NYT, Business Insider (Aug. 5, 2023), https://www.businessinsider.com/clarence-thomas-purchased-luxury-rv-with-help-of-healthcare-executive-2023-8.

[19] Becker & Tate, supra note 19; Julia Carbonaro, Who Paid for Clarence Thomas’ Motor Home? Meet Anthony Welters, Newsweek (Aug. 8, 2023), https://www.newsweek.com/clarence-thomas-motor-home-anthony-welters-1818131.

[20] Becker and Tate, supra note 19; Carbonaro, supra note 20.

[21] Heidi Przybyla, Law firm head bought Gorsuch-owned property, Politico, (Apr. 25, 2023), https://www.politico.com/news/2023/04/25/neil-gorsuch-colorado-property-sale-00093579.

[22] Jessica Schneider & Tierney Sneed, Justice Neil Gorsuch’s property sale to prominent lawyer raises more ethical questions, CNN (Apr. 25, 2023), https://www.cnn.com/2023/04/25/politics/gorsuch-property-sale-lawyer-ethics/index.html.

[23] Devan Cole, 2 Supreme Court justices did not recuse themselves in cases involving their book publisher, CNN (May 5, 2023), https://www.cnn.com/2023/05/04/politics/sonia-sotomayor-neil-gorsuch-book-recusal-supreme-court-cases/index.html; Nick Mordowanec, Conservatives Call Out Sotomayor’s $3M from Publisher Amid Thomas Reports, Newsweek (May 4, 2023), https://www.newsweek.com/conservatives-out-sotomayor-3-million-dollar-publisher-thomas-reports-1798460.

[24] Cole, supra note 26; Mordowanec, supra note 26.

[25] Cole, supra note 26; Mordowanec, supra note 26.

[26] See generally Cheney v. United States Dist. Court for the Dist. of Columbia, 541 U.S. 913 (2004) (Scalia, J., mem.); see also Monroe H. Freedman, Duck-Blind Justice: Justice Scalia’s Memorandum in the Cheney Case, 18 Geo. J. Leg. Ethics 229 (2004) (charactering Justice Scalia’s “opinion [as] both disappointing and disingenuous”).

[27] Cheney 541 U.S. at 916-20.

[28] Andrew Stanton,Democrat Sold First Republic Stock, Bought JP Morgan Before Collapse,” Newsweek (May 1, 2023), https://www.newsweek.com/democrat-sold-first-republic-stock-bought-jp-morgan-before-collapse-1797676; Haley Talbot, Democratic congresswoman sold First Republic stock and bought JPMorgan just before bank sale, financial disclosures show, CNN (May 2, 2023), https://www.cnn.com/2023/05/02/politics/democratic-congresswoman-first-republic-stock/index.html; but see Carter, supra note 8.

[29] Stanton, supra note 31; Talbot, supra note 31.

[30] Shirin Ali, The Tale of the Only U.S. Supreme Court Justice to be Impeached, Slate (May 8, 2023) https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2023/05/supreme-court-justice-impeachment-clarence-thomas-samuel-chase.html.

[31] Zach Schonfeld, Alito says Congress has ‘no authority’ to regulate Supreme Court, The Hill (July 28, 2023), https://thehill.com/regulation/court-battles/4125436-samuel-alito-on-congress-authority-to-regulate-supreme-court/.

[32] Brian L. Owsley, Impeaching Brett Kavanaugh, 55 U.S.F. L. Rev. Forum 479, 486-87 (2020); Ali, supra note 31.

[33] Owsley, supra note 37 at 487-88; see also Ali, supra note 35 (“Though the impeachment effort failed, historians believe that’s a good thing, because it could have set a dangerous precedent for presidents and Congress to simply look to impeachment if they didn’t approve of a sitting justice. It was seen as a win for judicial independence.”).

[34] Brian L. Owsley, Due Process and the Impeachment of President Donald Trump, 2020 Ill. L. Rev. Online 67, 68-69 (Apr. 17, 2020); Owsley, supra note 33 at 483-84.

[35] Todd Ruger, Justices to make rare appearance before appropriators, Roll Call (Mar. 1, 2019), https://rollcall.com/2019/03/01/justices-to-make-rare-appearance-before-appropriators/.

[36] Devin Dwyer, House ethics bill would require Supreme Court to adopt code of conduct, ABC News (Mar. 8, 2019), https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/house-ethics-bill-require-supreme-court-adopt-code/story?id=61556981.

[37] Lauren Fox & Tierney Sneed, Durbin invites Chief Justice John Roberts to testify on Supreme Court ethics before a Senate committee, CNN (Apr. 20, 2023), https://www.cnn.com/2023/04/20/politics/durbin-supreme-court-ethics-john-roberts/index.html.

[38] Ariane De Vogue, Justices Kennedy and Breyer Testify at House Appropriations Hearing, ABC News (Apr. 14, 2011), https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/justices-kennedy-breyer-testify-house-appropriations-hearing/story?id=13376677.

[39] Andrea Seabrook, Justices Get Candid About The Constitution, NPR (Oct. 9, 2011), https://www.npr.org/2011/10/09/141188564/a-matter-of-interpretation-justices-open-up.

[40] See generally U.S. Const. art. III, sec. 1.

[41] Chad Oldfather & Todd C. Peppers, Judicial Assistants Or Junior Judges: The Hiring, Utilization, And Influence of Law Clerks, 98 Marquette L. Rev. 1 (2014); How The Court Works—Law Clerk, Supreme Court Historical Society, https://supremecourthistory.org/how-the-court-works/law-clerks/.

[42] Todd C. Peppers, A Secretary’s Absence For A Law School Examination, 10 J. L.: Periodical Lab’y of Leg. Scholarship 259, 261-62 (2020); J. Daniel Mahoney, Law Clerks: For Better Or For Worse?, 54 Brook. L. Rev. 321, 322-23 (1988).

[43] Peppers, supra note 47, at 261; Mahoney, supra note 47, at 322-23.

[44] Peppers, supra note 47, at 261; Mahoney, supra note 47, at 323.

[45] 24 Stat. 254 (1886); Mahoney, supra note 47, at 323-24.

[46] 28 U.S.C. § 675.

[47] See Fredonia Broadcasting Corp. v. RCA Corp., 569 F.2d 251, 255-56 (5th Cir. 1978) (“The association with law clerks is also valuable to the judges; in addition to relieving him of many clerical and administrative chores, law clerks may serve as sounding boards for ideas, often affording a different perspective, may perform research, and may aid in drafting memoranda, orders, and opinions.”).

[48] How The Court Works—The Court’s Workload and Staff, Supreme Court Historical Society, https://supremecourthistory.org/how-the-court-works/court-workload-and-staff/; How The Court Works—Clerk of the Court and the Marshall, Supreme Court Historical Society, https://supremecourthistory.org/how-the-court-works/clerk-of-the-court-and-the-marshal/.

[49] How The Court Works—Law Clerks, Supreme Court Historical Society, https://supremecourthistory.org/how-the-court-works/law-clerks/.

[50] 28 U.S.C. § 674.

[51] How The Court Works—Library Support, Supreme Court Historical Society, https://supremecourthistory.org/how-the-court-works/library-support/.

[52] 28 U.S.C. § 671(a).

[53] How The Court Works—The Court’s Workload and Staff, supra note 53.

[54] 28 U.S.C. § 671(c); How The Court Works—Drafting and Releasing Opinions, Supreme Court Historical Society, https://supremecourthistory.org/how-the-court-works/drafting-and-releasing-opinions/.

[55] 28 U.S.C. § 677.

[56] Press Release, United States Supreme Court (Oct. 3, 2022), https://www.supremecourt.gov/publicinfo/press/pressreleases/pr_10-03-22; Tony Mauro, The Marble Palace Blog. What does a Counselor to the Chief Justice Do? Nat’l L. J. Online (Oct. 24, 2022), https://www.law.com/nationallawjournal/2022/10/24/the-marble-palace-blog-what-does-a-counselor-to-the-chief-justice-do/.

[57] 122 Stat. 4254 (2008); accord Mauro, supra note 61.

[58] Mauro, supra note 61.

[59] Id.

[60] 28 U.S.C. § 672.

[61] 28 U.S.C. § 672(c); How The Court Works—Clerk of the Court and the Marshall, supra note 53.

[62] Id.

[63] 28 U.S.C. § 672(c)(8); How The Court Works—Clerk of the Court and the Marshall, supra note 53.

[64] How The Court Works—Clerk of the Court and the Marshall, supra note 53.

[65] U.S. Const. art. II, sec. 2 (The President “with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law.”).

[66] U.S. Const. art. I, sec. 8, cl. 9 (“The Congress shall have Power … To constitute Tribunals inferior to the supreme court.”); U.S. Const. art. III, sec. 1 (“The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.”).

[67] U.S. Const. art. I, sec. 2 (“The House of Representatives … shall have the sole Power of Impeachment.”); U.S. Const. art. I, sec. 3 (“The Senate shall have the sole Power to try all Impeachments.”).

[68] U.S. Const. art. I, sec. 8, cl. 1.

[69] United States v. Butler, 297 U.S. 1, 66 (1936); accord South Dakota v. Dole, 483 U.S. 203, 207 (1987) (quoting Butler).

[70] Dole, 483 U.S. at 206.

[71] Id.; see also Nat’l Fed’n of Indep. Bus. v. Sebelius, 567 U.S. 519, 537 (2012) (“in exercising its spending power, Congress may offer funds to the States, and may condition those offers on compliance with specified conditions.”) (citation omitted).

[72] Dole, 483 U.S. at 207; see also Helvering v. Davis, 301 U.S. 619, 640 (1937) (“Congress may spend money in aid of the ‘general welfare.’”) (citations omitted).

[73] Dole, 483 U.S. at 207; see also Helvering, 301 U.S. at 640 (“The discretion, however, is not confided to the courts. The discretion belongs to Congress….”); Mathews v. De Castro, 429 U.S. 181, 185 (1976) (same).

[74] Mathews, 429 U.S. at 185 (quoting Helvering, 301 U.S. at 640).