Editor’s note: This week marks the 100th anniversary of Lena Olive Smith, a Mitchell Hamline legacy alum, becoming the first Black woman to become a licensed attorney in Minnesota. She remained the only Black woman lawyer in the state from 1921-1945. The following article was adapted by Tom Weber from a biography of Lena Olive Smith written by Mitchell Hamline professor Ann Juergens. Lena Olive Smith represents the highest values we aspire to as a law school, and Mitchell Hamline looks forward to continuing to celebrate her legacy more in this year.

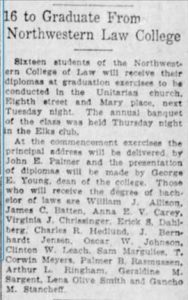

Graduation photo of Lena Olive Smith (Minnesota Historical Society photo)

In the days before bar exam passage was required to be a practicing lawyer in Minnesota, a person could graduate law school and be admitted to practice during the same week.

That’s what happened 100 years ago this week, when a 36-year old former real estate agent and failed undertaker named Lena Olive Smith became the first Black woman to be licensed to practice law in the state.

On the evening of Tuesday, June 14, 1921, Smith and 15 classmates gathered at a Unitarian church in downtown Minneapolis for a graduation ceremony for the Northwestern College of Law, one of the legacy schools that became Mitchell Hamline. Two days later, the Minnesota Supreme Court admitted 23 new lawyers – including Smith – to practice. The bar exam was in its infancy, making Smith’s group one of the last to gain admittance without it.

Minneapolis Tribune article from June 1921, announcing the pending graduation for Northwestern Law College

The licensure of the first Black woman to be a lawyer in Minnesota would be an important first to note today but it produced almost no attention in the press at the time, including from Black-owned newspapers.

This week, Mitchell Hamline School of Law is recognizing Lena Olive Smith for her career and contributions to the law that make her one of our most esteemed alumni.

Life’s Work

Her focus was to find ways to challenge discrimination in Minnesota; this began even before she became licensed to practice. Shortly after she began law school in 1916, she and four Black men together entered the Pantages Theater in downtown Minneapolis, knowing it had a policy to ask Black patrons to sit upstairs. When the five of them refused to take seats in the balcony and insisted on the main floor, they were denied admission. Each of them sued under a Minnesota law that forbid discrimination in public accommodations. Smith represented herself at trial and lost, but the group won the larger war. Publicity led the theater to end its segregation policy.

Lena Olive Smith and client at Olive Hair Store, Nicollet Avenue, Minneapolis (Minnesota Historical Society photo)

Born the oldest of five children in Kansas in 1885, Smith moved with her mother and younger siblings to Minneapolis after Smith’s father died in 1906. She tried many jobs to help support the family, from a “dramatic reader” to going to embalming school. Facing difficulty finding employment with an undertaking firm, she then opened a hair salon on Nicollet Avenue with a white woman partner. After the salon failed, Smith turned to real estate. This decision illustrates her feistiness, as this was a profession that few women took up at the time.

Work as a real estate agent for a year or two likely influenced Smith’s decision to begin attending law school at night. Real estate practices were an area where disparate treatment based on race was overt and common.

Racist property practices

Minnesota’s veneer of good law and professed lack of prejudice often masked racist social practices. Segregation, insult, and exclusion were in fact widespread. They flourished quietly at restaurants, department stores, movie theaters, and hotels.

In real estate the stakes for the Black community were especially high: they were cheated, denied access, and charged thousands more for property in desirable areas than were white people. Covenants also were written into thousands of property deeds to prevent homeowners from selling to anyone who wasn’t white.

And so, after graduating from law school and exactly 11 days after being sworn into the bar, Smith sued in Hennepin County District Court on behalf of an older Black couple who were being refused title to their home after paying for 25 years on their contract for deed. She tried the case to a jury and won. This case meant a lot to Smith; it was an encouraging start to her career as a lawyer and fighter for equitable treatment for members of her race.

Smith was an early member of the Minneapolis NAACP, formed in 1914, and stayed involved to the end of her life. The NAACP led people to Lena Smith’s door; she then used her skills to open other doors for them, sometimes for pay, sometimes without payment.

The Lee Family

Lena Olive Smith (Minnesota Historical Society photo)

Her most famous case came in 1931, when the Lees, a Black family, bought a house at 4600 Columbus Avenue in Minneapolis, knowing it was across an imagined color line. They had consulted with Smith, then the president of the Minneapolis NAACP, before doing so, yet were not certain of all they would face by breaking the taboo.

They knew children might harass them but did not believe the adults would join. During a hot July week, thousands of people milled about outside the house. They gathered each night to terrorize the Lees, hoping that hate and fear would convince them to vacate the house they had moved into only weeks before. The mob of white neighbors shouted threats to burn them out. The family dog was poisoned, and the throng jeered every time a person left the house. They threw stones and paint, feces, and firecrackers at the house as the Lees and about 20 of their supporters defended it, guns in hand.

Smith eventually came to represent the Lees, pro bono. She spoke forcefully with elected officials – including the governor, Floyd Olson, a fellow Northwestern Law alum – advocating the Lees’ right to stay in their home and the city’s responsibility to keep them safe and restore public peace.

In late July, after a weekend of meetings, Smith made an unflinching statement in the newspapers: Either the white citizenry would leave the young Black family in peace, or she would ask Governor Olson to call out the National Guard to disperse them. She and the national office of the NAACP also had exhorted the mayor and police chief to enhance police patrols at the house. She made clear that the Lees would not be leaving their new home. They have a right to establish a home where they wish, she announced, and the mayor and police chief have promised more vigorous protection.

Several dozen police were sent to protect the Lees. The volatile situation drew national attention. Though demonstrations continued, they eventually subsided.

Smith’s reputation as an effective lawyer who could not be bullied was enhanced in this dispute, as she helped a family resist the threats of white homeowners and the entreaties of government agents. It is worth noting that she did not turn to the courts, for the law was not clearly on the Lees’ side (except, perhaps, for laws against vandalism).

Lena Olive Smith (Minnesota Historical Society photo)

Yet Smith did not avoid court when necessary. In criminal law, Smith’s reputation grew when she confronted prosecutors who made explicit appeals to racial prejudice in their arguments. She won one motion for a new trial on a rape charge after a prosecutor asked the all-white male jury “Are you gentlemen going to turn this Negro loose to attack our women?”

Standing up with the Lees and the NAACP to the white supremacist mob highlighted the racism in Minnesota that is often hidden. And though housing in Minnesota remains quite segregated, the Lees’ courage—bolstered by Lena Smith and the NAACP — is an example to the community into the present day. Their house was named to the National Register of Historic Places as a marker of its significance in the struggle against racism.

Smith never married nor had children and lived with and supported her mother until Geneva died. She was dedicated to her work, to her extended family, and to her community in south Minneapolis, where her modest home is also listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Her work in later years was less prominent publicly, but she remained involved in many organizations, including the Minnesota State Bar Association. She died in 1966, at age 81, on a day when she was due in court. Her cellar was filled with fruits and vegetables that she had canned for the winter.

Smith’s contributions to the community were many, but perhaps her greatest contribution is this: she saw injustice and gave her clients the choice and the means to resist it.

Additional resources

William Mitchell Law Review article by professor Ann Juergens (2001)

MNopedia article (via Minnesota Historical Society) on Lena Olive Smith

Minnesota’s first black woman lawyer fought issues familiar today (Star Tribune, 2015)

Hennepin History Magazine article on Lena Olive Smith (1995)