Professor Ann Juergens

If you’re a renter and you discover mold in your apartment, is the landlord responsible for removing that mold quickly? It depends on the lease you signed and any city and state laws that apply where you live.

But how do tenants know which laws apply? Instead of hiring a lawyer to find out, a clinic at Mitchell Hamline is teaching students to create easy-to-build website tools that help people navigate these sometimes-tricky legal questions.

Students in the Housing Justice Chatbot-Building Clinic build online tools called chatbots to help people facing housing-related questions. They also find an organization to work with on these issues in their community.

“There’s a big difference between legal information and legal advice,” noted Ann Juergens, one of the two professors who teaches the clinic, which began in 2019. “A lot of times people with housing issues, like mold or a potential eviction, can’t afford to hire a lawyer to get even basic information.

“This lets us get that foundational information to people for free. From there, they can go seek legal advice, if needed.”

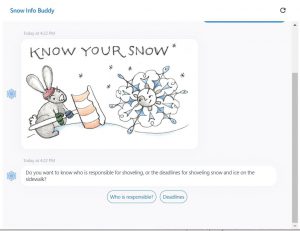

When someone clicks a link to a chatbot, they’re greeted with a series of multiple-choice questions. One example asks whether you’re a renter or homeowner. The answer that’s clicked or typed determines the next question. Eventually, after answering several questions, the goal is to present the user a baseline set of facts to educate them about the issue in front of them.

When someone clicks a link to a chatbot, they’re greeted with a series of multiple-choice questions. One example asks whether you’re a renter or homeowner. The answer that’s clicked or typed determines the next question. Eventually, after answering several questions, the goal is to present the user a baseline set of facts to educate them about the issue in front of them.

For students, creating a chatbot is easy and needs only basic technology savvy. Several apps already exist that allow people to create their own chatbots.

One student’s chatbot aimed to help renters in Minneapolis and St. Paul answer the question of who is responsible for clearing snow where they live. The mold issue noted above came from Stacie Wormley, who designed a chatbot to help people in her hometown of Charlotte, North Carolina, navigate the local ordinance that spells out when a landlord is responsible for removing mold.

Stacie Wormley

“Housing organizations were finding that people didn’t know there was an ordinance that required landlords to promptly address mold,” Wormley noted. “So they’d just keep living there until the mold got so bad, the landlord actually evicted them because so much remediation work was needed.

“Having a baseline knowledge of whether the landlord was responsible would have helped those tenants earlier in the process.”

For Lisa Needham ’02, the clinic’s other instructor, the course is about access to justice. “One chatbot isn’t going to solve homelessness or end evictions,” Needham noted. “But it will arm people with information they can use to advocate for themselves.

“Frankly, there aren’t enough lawyers out there to help every tenant who’s having a problem with their landlord, regardless of the costs to the client. So let’s find simple ways to get basic information to people, and they can go from there.”

While chatbots aren’t especially new technology, Needham and Juergens hope clinics like theirs show the need for lawyers and law schools to better align with technology to help clients – and to build upon the work Mitchell Hamline has done to be a leader in using technology to deliver legal education.

Chatbots can be used for any area of law and advocacy. During this summer’s protest in Charlotte after the killing of George Floyd, Wormley used her skills from the clinic to create a chatbot that offered information on voting and other advocacy around the Black Lives Matter movement. “The organizers didn’t just want to have a march and go home,” she noted. “This gave organizers a way to share actionable items with those who attended.”

Lisa Needham, one of the clinic’s instructors

Juergens and Needham foresee technology like chatbots helping with other matters, like evictions. “Imagine a chatbot that educated you on your rights in that situation,” Juergens opined. “Now imagine after answering a few questions on that page, it generates a form letter or email that a tenant could send to their landlord, detailing why they could not be evicted.”

The clinic limits enrollment to fewer than ten students; a third offering of the course will begin in January. “We can’t be gatekeepers who monopolize legal information anymore,” Juergens added. “All that information is out there online, so let’s use technology to marshal the necessary information into helping with one question at a time.”

For Wormley, who graduated in January 2020, the technology skills should prove helpful for her when she seeks her next job.

“I think it simplifies the law for people who may not understand it very well,” Wormley noted. “If you simplify the law to the most important question that needs addressing in that moment, that’s where the chatbot comes in.

“Take a chunk of law and simplify the big-ticket items for people.”