Dean Bruce Burton (Mitchell Hamline archives)

Bruce Burton, a former William Mitchell dean who led the school at a transformative time in its history, died on June 11, 2022, in Scottsdale, Arizona, where he lived. He was 83.

Burton served as dean from 1975 to 1980 and oversaw the school’s move to what is now the Mitchell Hamline campus. During his deanship, he also led a $4 million fundraising campaign and made several changes that professionalized both the board that governed the school and the faculty and staff who worked there.

“Dad loved the school with his heart and soul,” wrote Burton’s son Jeff, in an email this week.

The Fairmont, Minnesota, native graduated from Mankato State University in 1961, then taught high school English in Redwood Falls, Minnesota, and Long Beach, California, before returning to attend law school at the University of Minnesota.

After graduating in 1968, Burton joined what is now the Dorsey & Whitney law firm. He also taught as an adjunct at both the University of Minnesota and William Mitchell before joining Mitchell’s faculty full time in 1973.

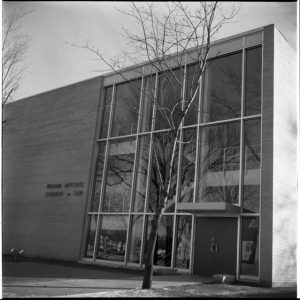

William Mitchell College of Law, as located at 2100 Summit Ave. in St. Paul (Minnesota Historical Society photo)

At the time, Mitchell was bursting at the seams in its location across from the College (now University) of St. Thomas. With a growing enrollment, Mitchell had to rent classroom space from the college and spent several years seeking a solution.

One option emerged at 875 Summit Avenue, a property that included a shuttered Catholic high school, Our Lady of Peace, and a convent. As Mitchell moved to buy it, a pastor in the Rondo neighborhood raised allegations of racism that his organization’s bid wasn’t accepted to buy the building for an interracial learning center for children.

Mitchell withdrew its initial offer on July 1, 1975, about a month before then-dean Doug Heidenreich was to resign. The school’s board had known about Heidenreich’s plans for a year but hadn’t searched for a new dean, citing a recommendation to not do so “until the board made some fundamental decisions about the kind and size of law school it wanted,” according to Heidenreich’s history of William Mitchell, “With Satisfaction and Honor.”

As a result, the purchase fell apart just as the school was about to be without a leader. Burton, an expert in real estate law, eventually agreed to be named acting dean. As a testament to the stress of the time, Heidenreich wrote that he was “off the hook” when Burton took over.

Eventually, the school resubmitted a bid that was accepted. The religious order that sold the building had cited concerns with the competing organization’s ability to raise the needed funds.

After completing the purchase, Burton launched and oversaw a $4 million campaign to raise the funds for buying and renovating Mitchell’s new home. “I remember running around the hallways and theater area of the old Our Lady of Peace school,” recalled Jeff Burton, who also was tasked with his sister Vicki with watering the lawn. “I was only seven or eight at a time, so of course, it was a blast.”

As renovations continued, Burton agreed to be named permanent dean – even though he had expressed no desire for the post – in May 1976. In August, a few weeks before classes were to begin, movers and volunteers shuttled thousands of books and other furniture and material to the new campus.

“I remember how hot it was [that day],” said Dave Savard, whose family lived on the same block as the Burtons, resulting in Burton hiring the young Savard and his brother to help with the move. Savard later was hired to work security, where he’s remained since. “Some of the nuns were still living in the convent as we were moving in,” he recalled. “I remember helping them move some of their belongings out.”

“I remember how hot it was [that day],” said Dave Savard, whose family lived on the same block as the Burtons, resulting in Burton hiring the young Savard and his brother to help with the move. Savard later was hired to work security, where he’s remained since. “Some of the nuns were still living in the convent as we were moving in,” he recalled. “I remember helping them move some of their belongings out.”

A formal dedication ceremony of the building was held in October 1977 and featured speeches from United States Chief Justice Warren Burger, an alumnus of St. Paul College of Law, a Mitchell predecessor school.

Burton’s time as dean also included removing a requirement that the board of trustees only include lawyers and judges as members. More people from the business community came in, which Heidenreich notes brought more professionalism from their corporate structures.

Burton also hired more support staff and renovated the leadership structure. More faculty were hired, and meeting and voting structures were enacted. A formal tenure code and student code were established, along with revisions to curriculum and graduation requirements.

Through its history, William Mitchell had always been a part-time night law school. In 1978, the first daytime course offerings began, which expanded the enrollment options for students.

“Bruce continued the upward trajectory of the law school,” said Professor Mike Steenson. “He was instrumental in the law school’s expansion and in hiring some of our most productive faculty members.”

With the changes came some headaches. Parking soon became an issue around campus. At one point, Mitchell’s student newspaper, the Opinion, ran a story about plans for a new parking ramp that would include a bar and disco in the basement. The story was satire but apparently not obviously enough to prevent the ire of the neighborhood. Burton was forced to publicly declare no such plans existed.

Bruce Burton, enjoying retirement in recent years (photo courtesy Jeff Burton)

In 1980, noting that his main task of establishing and paying for the law school’s new location was complete, Burton stepped down both as dean and faculty member. He later taught for 12 years at South Texas College of Law in Houston and, in retirement, served as a visiting professor at several law schools and was published in several journals. He also co-wrote a mystery novel called “Sleuth Slayer” with his son, Jeff, who is an author.

“He is remembered today as an enthusiastic, energetic, and effective dean who brought William Mitchell College of Law into the modern era,” wrote Heidenreich, in his book.

“He was the right person at the right time in the history of Mitchell,” added Professor Roger Haydock, who helped create the law school’s renowned clinics in the early 1970s. “He was a very serious guy who was a well-liked and well-respected attorney and professor, and he was fiercely loyal to the school.”

Burton is survived by his wife, Marlyse, six children, eight grandchildren, and one great-grandchild.